What is Food Culture?

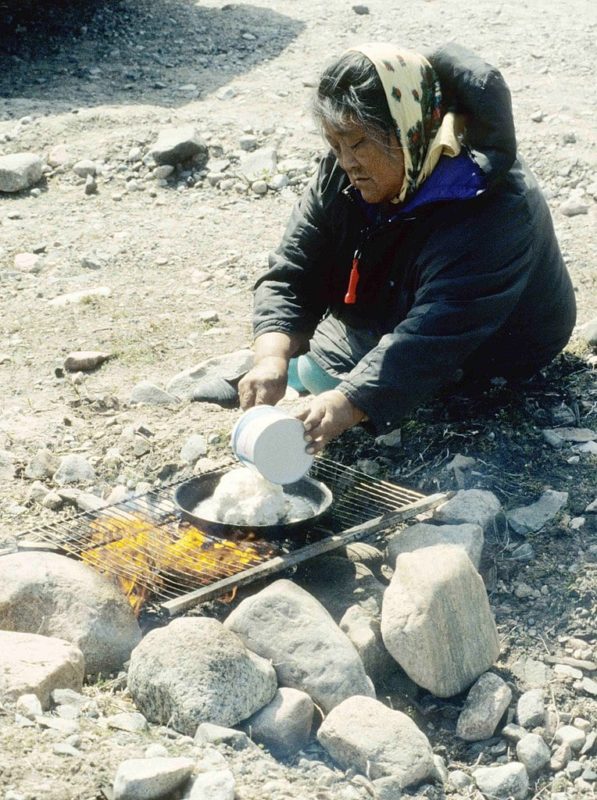

Food Culture can be defined as the attitudes, beliefs and practices that surround the production and consumption of food. Food Culture incorporates our ethnicity, and cultural heritage and provides a mechanism of communication with others both externally and within our families and communities.

Food anthropology is a sub-discipline within the field of anthropology and it is a critical part of understanding a culture. Culinary anthropologists have provided a greater understanding of broad societal processes such as politics, economics and value creation and the social constructs of collective memory. Simply put you cannot study a country and develop an ethnography of that culture without understanding the role food and food production have on all levels of the community.

Archaeologists search for evidence of culture through digs and ancient sites for the physical evidence left by previous cultures. They find clues about the past to learn how are ancestors lived and worked. A food anthropologist working with archaeologists investigate the food culture of the community through the remains of food left in firepits and found objects.

Food is the linchpin of society and it creates a connection between our beliefs, our ethnicity, our individual cultures and our cultural heritage. On a larger scale than most people realize, food is not just a part of the culture it can define culture.

Traditional foods and cuisine are passed down from one generation to the next within families and communities. In areas where the family or person has lost contact with their heritage one of the first places, they turn to are cooking schools or classes to learn what their cultural food traditions are.

Immigrants brought the food they grew up with to their new countries and in many cases passed these traditions down to their children. With war and conflict, however, many people became detached from their culture and their food culture.

It was impossible in some areas to obtain familiar ingredients and items that allowed our family recipes to be created. As a result, many communities created what has become known as micro-cuisine. This is a method of using local ingredients in familiar recipes that called for different traditional ingredients.

In many cases, regional cuisines are dependent on what can be grown within a specific area. We all know that corn, beans, squash and tomatoes along with chocolate came from the Americas and found the climates of warmer parts of Asia and Europe in which they could be grown.

In the Yucatan, for example, tamales are made with banana leaves wrapping them instead of corn husks. In Malaysia, the Baba Nyonya traditions incorporate the Chinese immigrants’ traditional dishes with local ingredients to create a micro cuisine. Parsi cuisine in India is a fusion of Iranian traditions with Indian cuisine.

What you eat and how you eat and when you eat can provide a lot of information about a specific culture. It also helps tell the stories of the people within those cultures. the study of micro-cuisines that are built upon immigrants’ adaptions of local ingredients is becoming a foodie trend.

As children, we grow up eating the specific foods of our cultures. For example, as a person born in the UK, I grew up eating canned baked beans as a vegetable which were served several times a week. This is not something that a person born in Canada would have eaten. We also ate potato pancakes or Boxty which are traditionally Irish along with Soda Bread. It was always a special day in our house when we had a full Irish breakfast – we always had this on Christmas morning and Easter.

We all know that a Jewish mother will prepare a great chicken soup also known as Jewish Penicillin for those with a cold. In the Philippines, the soup will contain rice instead of noodles and it contains a lot of ginger known as a remedy for nausea and a sore throat.

In some Asian countries, a big bowl of rice porridge is served and occasionally things like pickled plums or fish are added. Similarly in Pakistan, the porridge is a combination of rice and lentils called Khichdi.

In Eastern European countries like Russia or Poland, a giant bowl of borscht is prescribed and in Hungary, the remedy is garlic, and honey. Like many places across Western, Europe honey is used to soothe sore throats and is usually mixed with lemon.

In many countries, you can learn a lot about local culture simply by asking the vendors at street markets, the chefs and servers in restaurants. Observe the way the local people eat and order food in restaurants and follow their lead. In many hot Meditteranean countries, lunch is a large meal to fuel your day and dinner is eaten very late and may only consist of small bits like tapas.

These food culture traditions are handed down and become part and parcel of the various cultures to which they are attached. With various diasporas over the centuries, many cuisines have become part and parcel of their adopted homelands. Think Italian food in New York, Jewish cuisine in Montreal, and Chinese food traditions in the Western USA. Eastern European foods in the plains and prairies of Canada.

What always remains with that food culture though is the fact that it reflects its origins beliefs, values, unique history and lifestyles.

Local food culture gives people an identity

When you visit or live within another culture what you learn about food is also what you learn about the culture. Most locals are more than happy to share the stories of their cuisine and favourite dishes. For example in China harmony is critical to life and all the flavours must be balanced. So salty, sweet, bitter, sour and spicy are delicately balanced within every complex recipe.

For Chinese culture, it is critical for people to eat together from communal dishes and plates of food.

In the USA it was the indigenous people who taught the immigrants to use the available foods like corn, beans, squash and of course turkey. Over the centuries these have become entwined with new cultures arriving and are a traditional Thanksgiving dinner meal.

Latin America, Central America and Mexico gave the world chocolate, chillies, corn, beans, squash, potatoes and tomatoes along with lime. Mexican families often cook together a day of tamale preparation and other labour intensive dishes.

In Muslim and Indian countries no utensils are necessary it is believed that you taste the food more if you eat with your fingers. In the Western world we are accustomed to using a fork – but did you know that forks were once considered sacrilegious and viewed as an affront to god?

The use of chopsticks came about thanks to Confucius who believed that knives with their sharp pointy ends signified violence and reminded the eater of the slaughterhouse. Confucius was a strict vegetarian.

When you share food with locals or shop in local stores and actually converse with and engage with the locals you also hear their food stories. For example, in Mexico, corn tortillas are the staple in most of the lower regions of the country and in the Yucatan. Flour tortillas appear to have come about along the borders of Mexico and the original territories of the country which became the USA.

In Italy, there are many different ways to prepare and serve pasta, pizza and bread and each region has specific ingredients that they use in traditional recipes. In Northern Italy, polenta and risotto are more popular than pasta. Central Italy tends to use tomatoes, every kind of meat and offal, fish and pecorino cheese. In Southern Italy peppers, olives and olive oils, artichokes, oranges and anchovies are critical to the local recipes.

In Africa which is not a monolithic country, the cuisine varies widely from East to West, North and South. Traditionally the food of Africa uses available fruits, local vegetables, and grains. In some areas meat is not traditional as it is considered as good as cash and you don’t eat your money.

The Maasai are an exception as their traditional food culture is based almost entirely on the milk, meat and blood of their cattle.

Since much of Africa was colonized by western nations these cultural influences have developed foods that include ingredients that were not indigenous to the country but developed as a cash crop.

Of course, much great food arises out of poverty and food cultures have been impacted by the lack of availability of ingredients and the use of ingredients that were not considered edible by the ruling classes. Soul Food in the USA is a perfect example of this. Slaves created a food culture by using the ingredients they were “allowed” pork hocks and head, offal, cornbread and greens with fatback.

How to learn a region’s food culture

The best way to learn about a country is to study its food culture. How do you do that? Well here are 12 things you can do to learn about a country’s food culture.

- Take a cooking class

- Take a food tour

- Head to the local grocery stores

- Visit the local markets

- Explore restaurants offering local food

- Get recommendations from bloggers who focus on food

- Talk with your servers and chefs ask for their recommendations

- Ask for samples and taste everything

- Don’t eat in restaurants that have English signs venture further afield

- Learn about the local food “rules” for dining

- Research before you go and put together a list of recommended dining places

- Head to a local street food scene and eat

No one who cooks cooks alone. A cook in the kitchen is surrounded by generations of cooks past, the advice and menus of cooks present, the wisdom of cookbook writers. Laurie Colwin Gourmet Magazine

Love food? Want to explore more and learn about food around the World? Join me in my never-ending quest to learn everything I can about food.

You might also like

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage – food

59 Traditional British Foods – from the sublime to the WTF

French Food Culture: The Ultimate Guide

Armenian food – 45 Armenian dishes you must try

36 Traditional Egyptian Foods to whet your appetite

Food in Malta – the ultimate guide